Eye for an ear festival: Film Screenings / Presentations / Lectures

MALTE STEINER / WAJID YASEEN / ANDREI SMIRNOV / DEREK HOLZER / SANDRA NAUMAN / ROB MULLENDER / J MILO TAYLOR

THESE LECTURES ARE FREE TO ATTEND AND ARE A PART OF THE EYE FOR AN EAR FESTIVAL NO REGISTRATION NECESSARY!

————————————————

Monday June 24th

Malte Steiner: Realtime Audio Visual Performances with a Game Engine

17:30-18:30 Presentation of recent work with the open source game engine Panda3D programmed in Python and can import complex, bone controlled animations which can be made for instance with Blender. Triggerd via OSC messages it can be controlled from external software like Pure Data, Max4Live, Csound and many more. This presentation also shows briefly the Python scripting and the content creation with Blender.

https://www.panda3d.org/

http://www.block4.com/index.php?id=1&MP=1-11

WAJID YASEEN @ 19:30 – 20:30

‘transmodality and the sonic body’ How the body integrates our senses to make a meaningful understanding of any given experience in the world, and that the degree of cross-modal integration ie how much one sense modulates another, is highly idiosyncratic conveyed with examples of sound and visual crossover.

——————————————————

Wednesday June 26th

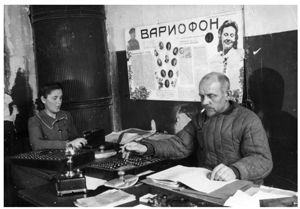

Andrei Smirnov: Music out of Noise, Light and Paper

history and culture of the Russian artistic Utopia of the 1910-1920s – a kind of ‘network culture’ of revolutionaries in art who realized seemingly unrealizable projects in sound, invented new musical machines, and who explored concepts and methods that offered a promising basis for future scientific and cultural development. The late 1920s was also the period in which sound was being developed to accompany films and animations in Russia and during the work on the first Soviet sound-on-film movie “Piatiletka. The Plan of the Great Works” in October 1929 the idea of artificially synthesized sound tracks was formulated. It was Avraamov who completed the first artificial drawn sound tracks in 1930 and b y 1 936 there were four main trends of Graphical Sound in Soviet Russia: hand-drawn Ornamental Sound (Avraamov, early Boris Yankovsky); hand-made Paper Sound (Nikolai Voinov); Variophone or automated Paper Sound (Evgeny Sholpo, Georgy Rimsky-Korsakov); and the spectral analysis, decomposition and re-synthesis technique (Boris Yankovsky). Yankovsky’s idea was related to the separation of the spectral content of sound and its formants, resembling the popular recent computer music techniques of cross synthesis and the phase vocoder. It was certainly one of the most radical, paradigm-shifting propositions of the mid 1930s.

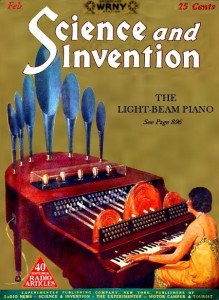

DEREK HOLZER: “A Brief History of Optical Synthesis”

The technology of direct optical synthesis arose with the first sound-on-film motion pictures. In the 1930′s, several designs for optical synthesizers were produced in the USSR, Germany and United States, with a handful even being commercially realized with to great amount of techno-utopian hype. The future of sound, we were assured, was made of light.

However, the use of optical synthesis for electronic music creation was largely abandoned after the Second World War in favor of techniques derived from new military technologies which made the V2 rocket and the atomic bomb possible. Thus, contemporary research into optical sound synthesis represents a media-archaeology of “the road not taken”, that of a connection to the culture of film and music versus the science of destruction and death.

http://www.umatic.nl/tonewheels_historical.html

——————————————————

Thursday June 27th

Sandra Nauman: Seeing Sound – Mary Ellen Bute (1906–1983) 16mm screenings

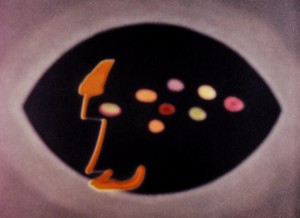

“In the 1930s Mary Ellen Bute belonged to the pioneers of abstract film in the USA; in the 1950s she was one of the first filmmakers to explore the possibilities of electronic image generation. In her short films she began to transfer the principles of musical composition to the creation of visual materials and tried various ways of linking sound and image.

Searching for a suitable medium for her vision of kinetic light art, Bute first experimented with devices to transmit acoustic into optical signals before she discovered film as her ideal medium of expression. Starting with RHYTHM IN LIGHT (1934) she first produced a series of black-and-white films where she coordinated distorted images of everyday objects with classical music. In the late 1930s she turned to animation techniques and early colour film techniques; the free creation of form and colour allowed her to open up a whole new spectrum of linking acoustic and visual elements which she continued to develop in films like TARANTELLA (1940) and POLKA GRAPH (1947). Later, in films such as ABSTRONIC (1952) and MOOD CONTRASTS (1953), she combined animated images with figures she generated from synchronised music by using an oscilloscope.” (Sandra Naumann)

Films being shown:

Abstronic 6 min / color rhapsody 6 min / dada 2 min / imagination 3 min / mood contrast 7 min / new sensations in sound 2 min / parabola 9 min / pastoral 7 min/ polka graph 4 min / rhythm in light 5 min / spook sport 8 min / tarantella 5 min

Still from “Abstronic” (1952) – courtesy Cecile Starr

Rob Mullender: Guy Sherwin’s Optical films 16mm screenings

Guy Sherwin Studied painting at Chelsea School of Art in the late 1960s. His subsequent film works often use serial forms and live elements, and engage with light and time as fundamental to cinema. Recent works include performances that use multiple projectors and optical sound, and installations made for an exhibition space. Sherwin taught printing and processing at the London Film-Makers’ Co-op (now LUX) during the mid-70s. His films were included in ‘Film as Film’ Hayward Gallery 1979, ‘Live in Your Head’ Whitechapel Gallery 2000, ‘Shoot Shoot Shoot’ Tate Modern 2002, ‘A Century of Artists’ Film & Video’ Tate Britain 2003/4. He lives in London and teaches at Middlesex University and University of Wolverhampton. His book with dvd ‘Optical Sound Films 1971-2007′ was published by LUX in 2007.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLsUhFawsZ8

http://vimeo.com/55777416

courtesy of Guy Sherwin & lux london

J Milo Taylor: Snooky the Chimp (#8 You’ll be Surprised) 8 mm

An anti-work. a counter-score. an audio-visual exploration of obsolescence, transformation and media anarchaeology.

This piece originated in the sudden increase in rent and resulted loss of home and working studio of close artisan friend due to the ongoing gentrification in East London. The Olympic Games were very much part of this homogenising profiteering, but the trend is much more deeply experienced throughout an area in which many of us first met and began to produce our anti-art. The sudden necessity for my friend to move his workshop, studio, storage space and home of 20 years resulted in a mass of media related material being offered at short notice to his immediate community. (slide projectors, amplifiers, 8 track cartridges, minidisc players, vinyl, cassettes, VHS, smoke machines, lighting systems, recording desks, outboard effects, tone generators, Super 8 films). Much of this material, gathered over a years in a life of underground music and experimental performance. Was simply given away – it’s sheer mass being overwhelming under these circumstances. In such a way, the visual material that forms the basis of this piece (a collection of Super 8 film) was gathered.

These films were experienced, and when a particularly striking sequence was found, the projector rewound and a manual edit made – the edited footage then assigned into one of an arbitrary 8 categories. In the course of this process, it became clear that in working with the Super 8 material that the medium afforded a translation between time and space. The various lengths of film equated to periods of time – space had become time. The various projection speeds commonly associated with Super 8 (18fps, 24 fps) results in the following:

8mm x 18 = 144mm

8mm x 24 = 192mm

The usual convention of editing material, according to the base reference of the frame as an elementary unit, was avoided in the piece. Instead, the base material is organised according to a Fibonacci sequence, expressed in cm. According the film is based upon a repeated rhythmic pattern of the follow spatio-temporal durations.

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 56 cm

Which then, depending upon the projector speed equate to the following durations.

material from each of these categories was then autonomically resequenced

The sonic elements of the film occur in real-time and are generated by home assembled electronic circuits responding to the variations in the light intensity of the film images and the ambient space. The frame is mapped by a 3 x 4 matrix of cheap sensors which cross modulate a number of sonic variables (amplitude, pitch, oscillation rate, eq, pan) in response to the changing (and somewhat indeterminate) state of the visual sequence.

I take as a theoretical position that considers the sonic as a tangible element of material culture – past, present and futures. I am much influenced by German media archaeology, notably associated with Kittler and Zeienslinki, but taken up and expanded upon more recently by young thinkers and writers such – such work seemly focused upon the Northern European discourse. Such area have become increasingly interesting to me since a Research Fellowship at the Kunsthhochschule fur Medien Cologe (kdm.de) where the object of study was a found array of 78rpm shellac recordings. This contingent sample of sonic artefacts was

A key motivation for undertaking this work was the inspiration provided by Volker Muller, technician of the WDR Electronic Studios, Cologne. Watching him demonstrating several techniques fort he manipulation of sound with several 4 track reel to reel machines (as articulate by such luminaries of the historically progressive sonic culture of the city as Stockhausen and the artists, musicians and composers associated with the WDR Electronic Studio, and its sister studio the Studio fur Akustsische Kunst led for many years by x. Experiencing Mueller’s (beint one with) these historical machines suggested to me that while access to these rare and complex machines was beyond my means – I might well be able to organise electronic sound using the Super 8 tape I had inherited.

Hence this piece explores the means of seeing and hearing and the technical structuring of the human sensorium in the variable material and discursive cultures which we have created and inhabit.

Objects and bodies – renewal and redundancy – property and ownership – the desirable and the undesirable. Signal and noise. Image and Medium. The analogue and the digital– or more accurately the continuous and the discrete.

This piece is aggressive in tone

The media body – meaningless and “narrativish”